Like classical economists before us, as product managers we often assume that users engaging with our applications are perfectly logical. Often both web applications and modern economic policies depend on a “homo-economicus,” or in other words, a completely rational user. However, evidence from behavioral economics suggests that this persona is a rare commodity in today’s digital landscape. Researchers in this field are now challenging conventional understandings of consumer behavior, demonstrating that we are predictably irrational. As modern-day product managers, it would be wise to leverage these latest insights when building our applications.

Lesson #1: Sometimes Less Really is More

Early economic theory argued that more choice was always a good thing, resulting in higher utility (or happiness) for all agents engaged in a transaction. Product managers typically see merit in offering our users as many options as possible. However, this approach may be misguided. Randomized controlled trials experimenting on market shoppers demonstrate the hidden risks of providing too much choice to individuals. In one study, when offering shoppers a preference between a larger and smaller assortment of goods, the vast majority of people showed more interest in the one with more options to browse. But this greater interest in the larger selection of goods did not translate into additional sales. Shoppers were ten times more likely to make a purchase if there were just six types of the product compared to 24 items. The implications for product management are clear — as PMs striving to drive conversions, we should aim to filter out the noise in our applications.

Takeaway: By offering quality features over quantity, we will aid in mitigating user paralysis and secure successful outcomes for both parties involved.

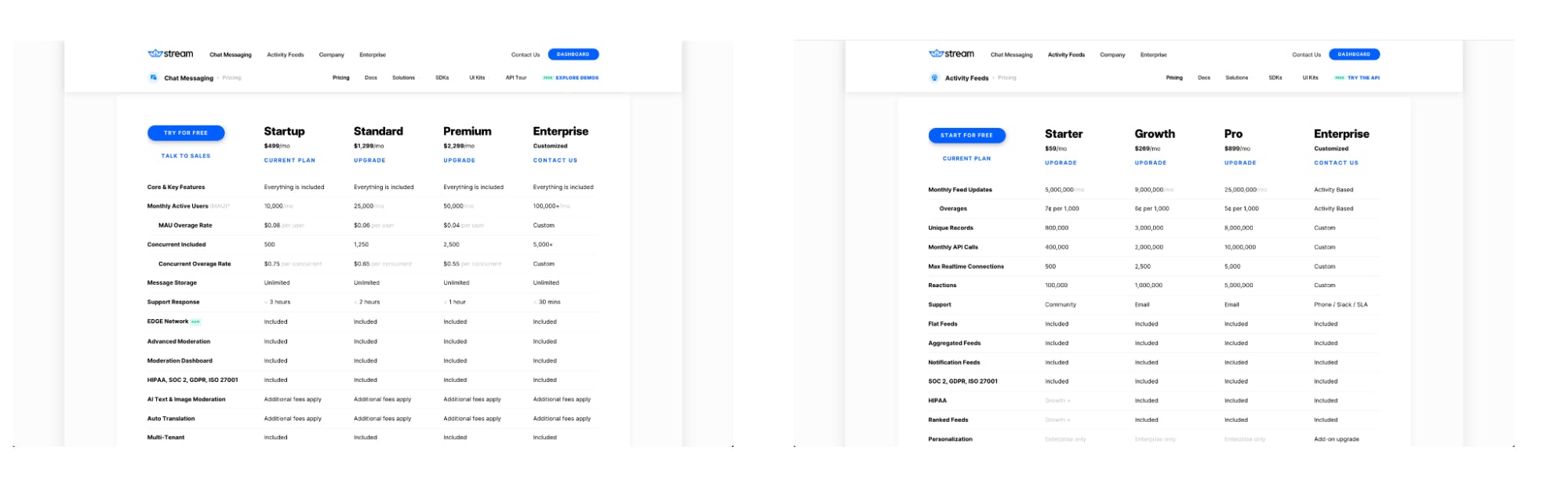

Stream simplified pricing options to reduce choice fatigue in our latest development cycle.

Lesson #2: Opt In vs. Opt Out

Organ donor participation drastically varies from country to country, even once cultural factors have been considered. A key difference in uptake is the policy-generated outcome requiring citizens to either “opt in” or “opt out” of being an organ donor. In Germany, for example, in order for individuals to become a donor, they are required to complete a lengthy and detailed form. Unsurprisingly, this mandated step results in only 12% of the population being registered donors. Alternatively, in Austria, the entire population is presumed to be a donor and must opt out by means of an equally tedious process. Consequently, a staggering 99% of the Austrian population are registered donors. As product managers, we can learn a lot about human behavior from this specific example looking at organ donor registration.

Takeaway: When building our applications, we should pay careful attention to what we set as the default. Our users will likely suffer from inertia and choosing something for them will likely stay as the status quo.

Lesson #3: All Is Well That Ends Well

Historically, economists argued that all aspects of a transaction were important for evaluating final consumer utility satisfaction. However, recent research suggests that this conclusion may be misguided. There is evidence indicating that human memory is largely biased to remember the lowest low or final moment of a situation. This has been demonstrated within healthcare, specifically within the field of colonoscopy. Practitioners in this realm have historically been faced with two options:

- Move as quickly as possible, keeping the procedure shorter but with higher surges of pain particularly at the end.

- Be slow and methodical, resulting in a longer procedure but with lower surges of pain particularly at the end.

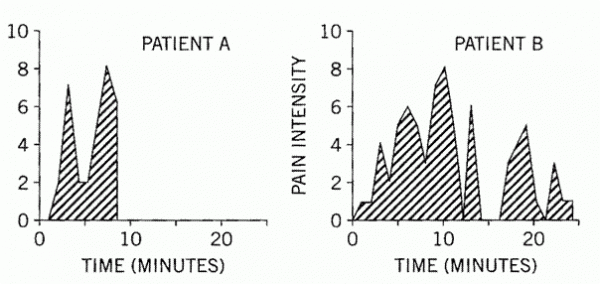

Most doctors chose to perform the rapid procedure, thinking this would be preferred by the patient as it results in less net pain. However, comparing patients undergoing similar medical operations, research shows overall pain during the procedure (rated in real time by patients through a keyboard) was irrelevant to how the experience was recollected afterwards. For example, despite the recordings below, patient A described their experience as much more painful both immediately after the operation and much later, even though the procedure only lasted around eight minutes.

This result seems strange because clearly patient B — whose procedure lasted almost 25 minutes — suffered more aggregate pain during the procedure. Patient A finished the procedure with a high intensity of pain versus patient B’s relatively low intensity ending. This difference was enough for patient A to believe they had a more painful procedure compared to B.

Takeaway: This finding is important for product management. When building our applications, we should pay particular attention to the last interaction a user has with our product before logging off. A warm-hearted message of appreciation is an easy way to accomplish this outcome. Leaving things on a positive note will likely be the difference between a repeat engagement or not.

A friendly sign-off from studiolos.com.

Apply Scientific Findings

As the field of behavioral economics continues to grow, even more implications for product managers will become clear. Those who embrace these findings within the scientific method will likely have the most success. Continuing to form hypotheses, experiment, learn, and test these findings within our products will ensure they are not taken at face value. For now, it seems we should keep applications as simple as possible, use defaults cautiously, and carefully manage the final interactions with our user.